MASSACHUSETTS - THE UNLIKELY BIRTHPLACE OF BASKETBALL AND VOLLEYBALL

|

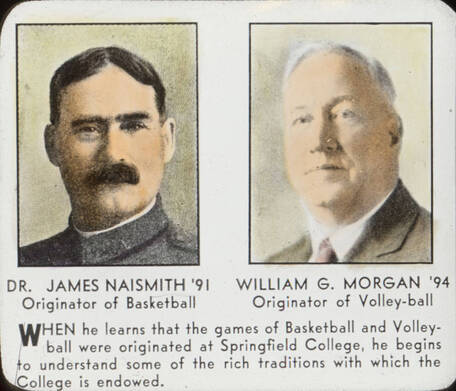

TWO OF THE MOST POPULAR SPORTS IN THE OLYMPICS – BASKETBALL AND VOLLEYBALL – EACH HAVE THEIR ORIGINS IN THE U.S. STATE OF MASSACHUSETTS WHERE THEY WERE DEVISED BY TWO PIONEERING PHYSICAL DIRECTORS IN THE LATE 19TH CENTURY.

James Naismith, an 1891 graduate of Springfield College (then the International YMCA Training School) taught at the college for five years during which time he created the game of basketball. Morgan, also a graduate of Springfield College, invented the game of volleyball in Holyoke, MA. Morgan was influenced by his teacher James Naismith and wanted to create a game that was less vigorous than basketball for the older members of the YMCA. Originally called Mintonette, the name was later changed to volleyball as suggested by Springfield College teacher Alfred Halstead. Use the tabs below to explore the history of basketball and the influence Naismith had on volleyball's founder. |

Courtesy of Springfield College, Babson Library, Archives and Special Collections. |

BASKETBALL'S INFLUENCE ON VOLLEYBALL

VOLLEYBALL FOUNDER INSPIRED BY NAISMITH

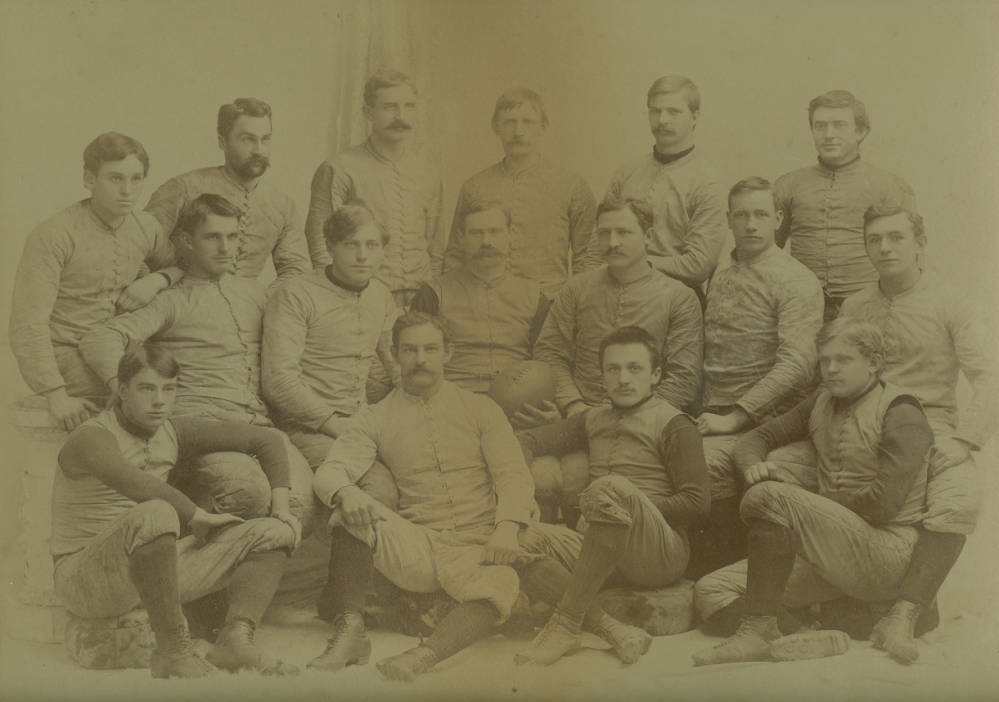

Courtesy of Springfield College, Babson Library, Archives and Special Collections.

A photograph of the Springfield College Football Team of 1892. Notable alums featured in the photograph are James Naismith and William Morgan. Naismith invented the game of basketball in 1891 while a faculty member of Springfield College (then the International YMCA Training School) and is listed as being the captain of the 1892 football team. Also in the picture are (back row L to R) P.S. Page, W.H. Kinnicutt, D.C. Stephens, C.B.F. Wall, Frank Mahan, L.W. Archibald, (middle row L to R) Louis Welzmiller, E.G. Hildner, James Naismith, F.N. Seerley, William G. Morgan, J.F. Black, (front row L to R) F.H. Foster, J.E. Badger, H.L. Smith, and W.E. Miller.

AN UNLIKELY MEETING

|

William Morgan invented the game of volleyball in 1895 while working as a physical director at the Holyoke YMCA in Holyoke, MA.

Naismith and Morgan first met during a football game in 1891 between the Training School, where Naismith was a player and coach, and the Mount Hermon School for Boys, where Morgan was a student. After the game, Naismith, impressed by Morgan's playing ability, encouraged Morgan to attend the Training School. Morgan obliged and graduated the Training School in 1894 and began work as a physical director, first at the Auburn YMCA in Maine and then at the Holyoke YMCA - located just 5 miles away from Springfield. |

William G. Morgan Portrait c. 1895 - Courtesy of Springfield College, Babson Library, Archives and Special Collections. |

A NEW GAME WAS BORN

|

Early volleyball at the Holyoke YMCA - Courtesy of the IVHF Archive |

The year was 1895 and Holyoke YMCA physical director William G. Morgan had a problem. The newly created game of basketball, while popular with the kids, was proving to be too strenuous for the local businessmen. He needed an alternative - something these older gentlemen could play - something without too much "bumping" or "jolting".

It had to be physical - playing a game, after work and at lunch time, should provide exercise, but it also had to relax the participants - it couldn't be too aggressive. It had to be a sport, Morgan said, "with a strong athletic impulse, but no physical contact." So, he borrowed. From basketball, he took the ball. From tennis the net. The use of hands and the ability to play off the walls and over hangs, he borrowed from handball. And, from baseball, he took the concept of innings. He termed this new game "Mintonette". And though admittedly incomplete, it proved successful enough to win an audience at the YMCA Physical Director's Conference held in Springfield, Massachusetts the next year. It was at this conference that Dr. Alfred T. Halstead, a professor at Springfield College, suggested a two-word version of its present name. "Volley Ball". And it stuck. |

ORIGINAL VOLLEYBALL RULES

|

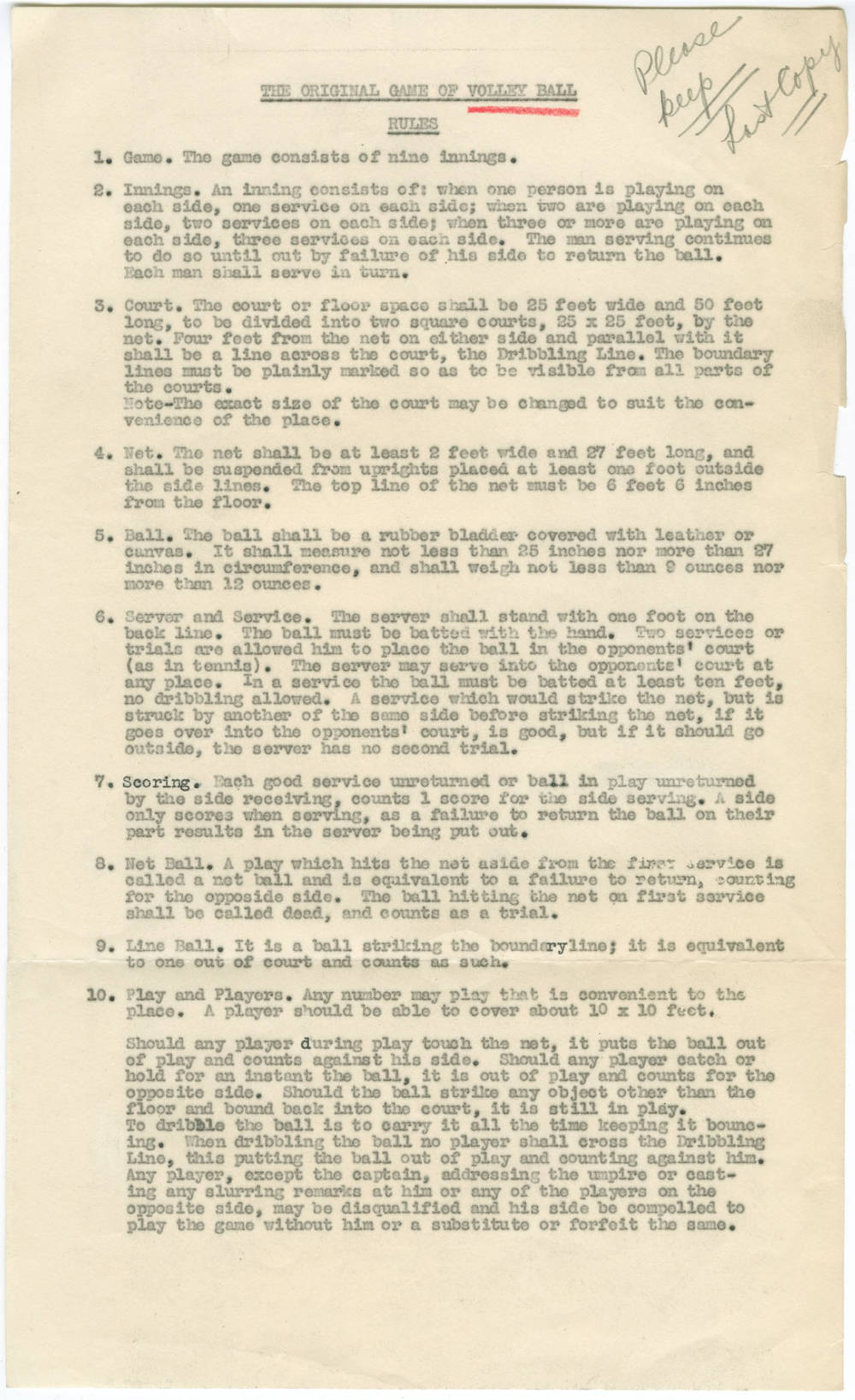

The game of volleyball was quite a bit different from what we're used to. It was played on a smaller 25'x50' court, with an unlimited number of players hitting the ball an unlimited number of times, on either side of a 6'6" high net. Things tended to get a little crowded.

Each game was broken up into nine innings, each inning made up of three outs, or "serves". These serves could be helped over the net by a second player, if the server didn't quite reach the net. The basketball originally used proved to be a little too heavy, and the subsequent use of a basketball bladder, too soft. Morgan remedied this by contacting A.G. Spalding, a local sporting goods manufacturer who designed a special ball - a rubber bladder, encased in leather, 25" or so in circumference. The "volleyball". Though still in its infancy, the sport was slowly developing and with the YMCA taking the reigns, Morgan was confident volleyball would continue to entertain and relax the boys down at the "Y". What he probably didn't realize was that he had just created what would become the second most popular team sport in the world. In 1916, the YMCA managed to induce the powerful National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) to publish its rules and a series of articles, contributing to the rapid growth of volleyball among young college students. In 1918 the number of players per team was limited to six, and in 1922 the maximum number of authorized contacts with the ball was fixed at three. Until the early 1930's volleyball was for the most part a game of leisure and recreation, and there were only a few international activities and competitions. There were different rules of the game in the various parts of the world; however, national championships were played in many countries (for instance, in Eastern Europe where the level of play had reached a remarkable standard). Volleyball thus became more of a competitive sport with high physical and technical performance. |

A copy of the original rules for the game of volleyball sent to Springfield College in 1932 from William Morgan, the inventor of volleyball. Courtesy of Springfield College, Babson Library, Archives and Special Collections. |

VOLLEYBALL'S OLYMPIC DEBUT

|

The history of Olympic volleyball can be traced back to the 1924 Summer Olympics in Paris, where volleyball was played as part of an American sports demonstration event. Though, Volleyball didn't make its Olympic debut until the 1964 Tokyo Games after being adopted by the International Olympic Committee as a non-Olympic sport in 1949. Eight years later, on September 24, 1957, the IOC session in Sofia recognized Volleyball as an Olympic sport and the FIVB as the sole worldwide Volleyball governing body in all its disciplines.

In 1961, Volleyball was approved to be included as a medal sport for men and women at the Tokyo Games in 1964. The Olympic Committee initially dropped volleyball for the 1968 Olympics, meeting protests. The number of teams involved in the games has grown steadily since 1964. Since 1996, both men's and women's indoor events count 12 participant nations. Each of the five continental volleyball confederations has at least one affiliated national federation involved in the Olympic Games. Brazil, United States, and the former Soviet Union, are the only teams to win multiple gold medals at the men's tournament since its introduction. The remaining five editions of the Men's Olympic Volleyball Tournament were won each by a different country including Japan, Poland, Netherlands, Russia and the defunct Yugoslavia. Gold medals are less evenly distributed in women's volleyball than in men's; the fourteen editions of the Women's Olympic Volleyball Tournament were won by only five different countries: Brazil, Cuba, China, Japan and the former Soviet Union. |

OLYMPIC BEACH VOLLEYBALL

|

Beach volleyball was introduced at the Summer Olympic Games in 1992 at the Barcelona Games as a demonstration event, and has been an official Olympic sport since 1996.

Brazil has won a gold or a silver medal (3 golds) at every Olympic beach volleyball tournament, in either the men's or women's tournament competition, since its introduction in 1996. The United States has also won at least a bronze medal (6 golds) in every men's or women's tournament in the same period. |

Misty May-Treanor (USA) at the 2008 Olympics |

HISTORY OF BASKETBALL

|

THE BIRTHPLACE OF BASKETBALL

Basketball is built into the fabric of Springfield College. The game was invented by Springfield College instructor and graduate student James Naismith in 1891 and has grown into the worldwide athletic phenomenon we know it to be today.

|

Courtesy of Springfield College, Babson Library, Archives and Special Collections.

|

|

Courtesy of Springfield College, Babson Library, Archives and Special Collections.

|

WHERE BASKETBALL ORIGINATED

It was the winter of 1891-1892. Inside a gymnasium at Springfield College (then known as the International YMCA Training School), located in Springfield, Mass., was a group of restless college students. The young men had to be there; they were required to participate in indoor activities to burn off the energy that had been building up since their football season ended. The gymnasium class offered them activities such as marching, calisthenics, and apparatus work, but these were pale substitutes for the more exciting games of football and lacrosse they played in warmer seasons.

|

JAMES NAISMITH, THE PERSON WHO INVENTED BASKETBALL

The instructor of this class was James Naismith, a 31-year-old graduate student. After graduating from Presbyterian College in Montreal with a theology degree, Naismith embraced his love of athletics and headed to Springfield to study physical education—at that time, a relatively new and unknown academic discipline—under Luther Halsey Gulick, superintendent of physical education at the College and today renowned as the father of physical education and recreation in the United States.

As Naismith, a second-year graduate student who had been named to the teaching faculty, looked at his class, his mind flashed to the summer session of 1891, when Gulick introduced a new course in the psychology of play. In class discussions, Gulick had stressed the need for a new indoor game, one “that would be interesting, easy to learn, and easy to play in the winter and by artificial light.” No one in the class had followed up on Gulick’s challenge to invent such a game. But now, faced with the end of the fall sports season and students dreading the mandatory and dull required gymnasium work, Naismith had a new motivation.

Two instructors had already tried and failed to devise activities that would interest the young men. The faculty had met to discuss what was becoming a persistent problem with the class’s unbridled energy and disinterest in required work.

During the meeting, Naismith later wrote that he had expressed his opinion that “the trouble is not with the men, but with the system that we are using.” He felt that the kind of work needed to motivate and inspire the young men he faced “should be of a recreative nature, something that would appeal to their play instincts.”

Before the end of the faculty meeting, Gulick placed the problem squarely in Naismith’s lap.

“Naismith,” he said. “I want you to take that class and see what you can do with it.”

So Naismith went to work. His charge was to create a game that was easy to assimilate, yet complex enough to be interesting. It had to be playable indoors or on any kind of ground, and by a large number of players all at once. It should provide plenty of exercise, yet without the roughness of football, soccer, or rugby since those would threaten bruises and broken bones if played in a confined space.

Much time and thought went into this new creation. It became an adaptation of many games of its time, including American rugby (passing), English rugby (the jump ball), lacrosse (use of a goal), soccer (the shape and size of the ball), and something called duck on a rock, a game Naismith had played with his childhood friends in Bennie’s Corners, Ontario. Duck on a rock used a ball and a goal that could not be rushed. The goal could not be slammed through, thus necessitating “a goal with a horizontal opening high enough so that the ball would have to be tossed into it, rather than being thrown.”

Naismith approached the school janitor, hoping he could find two, 18-inch square boxes to use as goals. The janitor came back with two peach baskets instead. Naismith then nailed them to the lower rail of the gymnasium balcony, one at each end. The height of that lower balcony rail happened to be ten feet. A man was stationed at each end of the balcony to pick the ball from the basket and put it back into play. It wasn’t until a few years later that the bottoms of those peach baskets were cut to let the ball fall loose.

Naismith then drew up the 13 original rules, which described, among other facets, the method of moving the ball and what constituted a foul. A referee was appointed. The game would be divided into two, 15-minute halves with a five-minute resting period in between. Naismith’s secretary typed up the rules and tacked them on the bulletin board. A short time later, the gym class met, and the teams were chosen with three centers, three forwards, and three guards per side. Two of the centers met at mid-court, Naismith tossed the ball, and the game of “basket ball” was born.

As Naismith, a second-year graduate student who had been named to the teaching faculty, looked at his class, his mind flashed to the summer session of 1891, when Gulick introduced a new course in the psychology of play. In class discussions, Gulick had stressed the need for a new indoor game, one “that would be interesting, easy to learn, and easy to play in the winter and by artificial light.” No one in the class had followed up on Gulick’s challenge to invent such a game. But now, faced with the end of the fall sports season and students dreading the mandatory and dull required gymnasium work, Naismith had a new motivation.

Two instructors had already tried and failed to devise activities that would interest the young men. The faculty had met to discuss what was becoming a persistent problem with the class’s unbridled energy and disinterest in required work.

During the meeting, Naismith later wrote that he had expressed his opinion that “the trouble is not with the men, but with the system that we are using.” He felt that the kind of work needed to motivate and inspire the young men he faced “should be of a recreative nature, something that would appeal to their play instincts.”

Before the end of the faculty meeting, Gulick placed the problem squarely in Naismith’s lap.

“Naismith,” he said. “I want you to take that class and see what you can do with it.”

So Naismith went to work. His charge was to create a game that was easy to assimilate, yet complex enough to be interesting. It had to be playable indoors or on any kind of ground, and by a large number of players all at once. It should provide plenty of exercise, yet without the roughness of football, soccer, or rugby since those would threaten bruises and broken bones if played in a confined space.

Much time and thought went into this new creation. It became an adaptation of many games of its time, including American rugby (passing), English rugby (the jump ball), lacrosse (use of a goal), soccer (the shape and size of the ball), and something called duck on a rock, a game Naismith had played with his childhood friends in Bennie’s Corners, Ontario. Duck on a rock used a ball and a goal that could not be rushed. The goal could not be slammed through, thus necessitating “a goal with a horizontal opening high enough so that the ball would have to be tossed into it, rather than being thrown.”

Naismith approached the school janitor, hoping he could find two, 18-inch square boxes to use as goals. The janitor came back with two peach baskets instead. Naismith then nailed them to the lower rail of the gymnasium balcony, one at each end. The height of that lower balcony rail happened to be ten feet. A man was stationed at each end of the balcony to pick the ball from the basket and put it back into play. It wasn’t until a few years later that the bottoms of those peach baskets were cut to let the ball fall loose.

Naismith then drew up the 13 original rules, which described, among other facets, the method of moving the ball and what constituted a foul. A referee was appointed. The game would be divided into two, 15-minute halves with a five-minute resting period in between. Naismith’s secretary typed up the rules and tacked them on the bulletin board. A short time later, the gym class met, and the teams were chosen with three centers, three forwards, and three guards per side. Two of the centers met at mid-court, Naismith tossed the ball, and the game of “basket ball” was born.

|

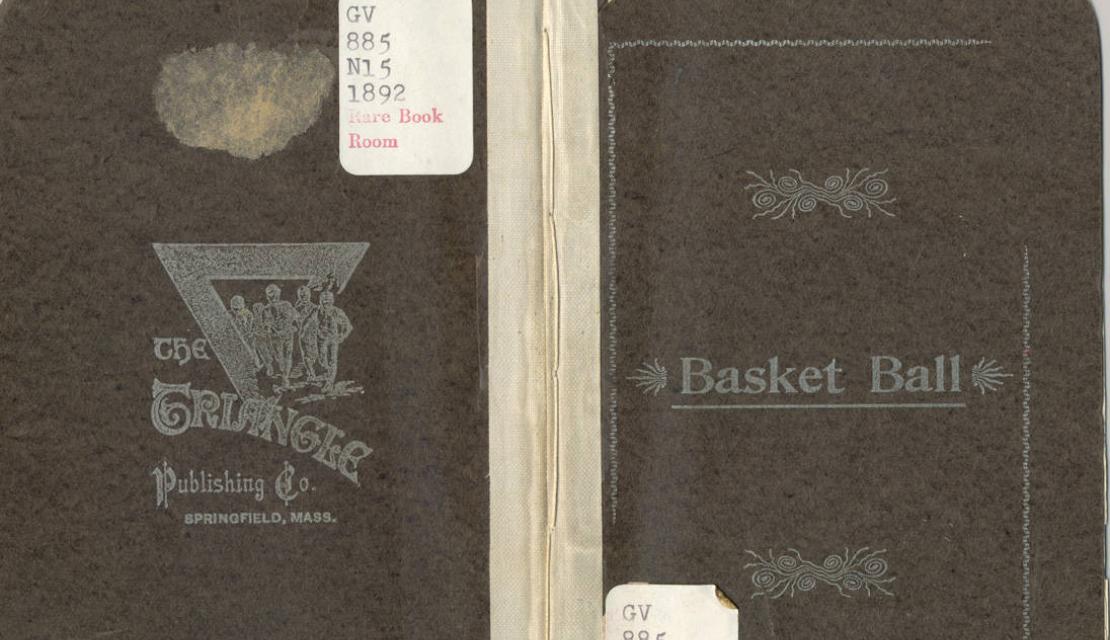

THE YEAR BASKETBALL WAS INVENTED

Word of the new game spread like wildfire. It was an instant success. A few weeks after the game was invented, students introduced the game at their own YMCAs. The rules were printed in a College magazine, which was mailed to YMCAs around the country. Because of the College’s well-represented international student body, the game of basketball was introduced to many foreign nations in a relatively short period of time. High schools and colleges began to introduce the new game, and by 1905, basketball was officially recognized as a permanent winter sport.

The rules have been tinkered with, but by-and-large, the game of “basket ball” has not changed drastically since Naismith’s original list of “Thirteen Rules” was tacked up on a bulletin board at Springfield College. |

Courtesy of Springfield College, Babson Library, Archives and Special Collections.

|

WHERE WAS BASKETBALL INVENTED?

|

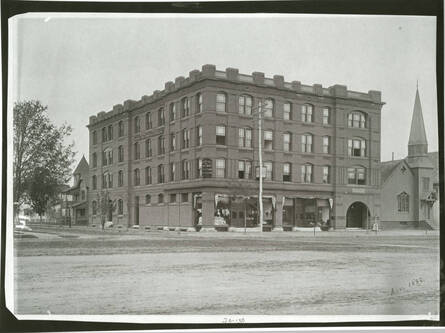

Courtesy of Springfield College, Babson Library, Archives and Special Collections.

|

There’s been some confusion over the precise nature of the official relationship between Springfield College and the YMCA, as it relates to James Naismith and the invention of basketball.

The confusion stems in part from changes in the School’s name in its early history. Originally the School for Christian Workers, the School early in its history had three other names which included “YMCA”: the YMCA Training School, the International YMCA Training School, and, later still, the International YMCA College. The College didn’t officially adopt the name “Springfield College” until 1954, even though it had been known informally as “Springfield College” for many years. But by whatever name, since its founding in 1885 Springfield College has always been a private and independent institution. The College has enjoyed a long and productive collaboration with the YMCA, but has never had any formal organizational ties to the YMCA movement. The confusion has been compounded by a small sign on the corner of the building where basketball was invented. The building stood at the corner of State and Sherman streets in Springfield, Massachusetts. The sign, carrying the words “Armory Hill Young Men’s Christian Association,” is visible in old photographs of the building that have circulated online. This has led some to believe, erroneously, that the Armory Hill YMCA owned the building, and that James Naismith was an employee of the YMCA. However, in 2010, some historic YMCA documents and Springfield College documents from the period were rediscovered. These documents prove conclusively that the gymnasium in which Naismith invented basketball was located not in a YMCA but in a building owned and operated by the School for Christian Workers, from which today’s Springfield College originated. The building also included classrooms, dormitory rooms, and faculty and staff offices for the institution. The Armory Hill YMCA rented space in the building for its activities, and used the small sign to attract paying customers. James Naismith, the inventor of basketball, was an instructor in physical education at the College. It was Luther Halsey Gulick, Naismith’s supervisor and the College’s first physical education director, who challenged Naismith to invent a new indoor game for the School’s students to play during the long New England winter. There is currently no evidence to suggest that either man ever worked for the Armory Hill YMCA, per se. So now you know the true story of James Naismith and the invention of basketball. |

BASKETBALL AND THE OLYMPIC GAMES

Naismith was 75 when he saw his sport make its Olympic debut in Berlin in 1936 and he was accorded the honor of throwing the jump ball at the opening match between France and Estonia. The tournament was held on outdoor courts and was won by the USA, who beat Canada 19-8 in a final played in very muddy conditions following prolonged heavy rain. The sport’s inventor was also asked to present the medals.

Over the following two decades, basketball’s growth was exponential. The USA’s professional basketball league, the NBA, was founded in 1946, while the first International Basketball Federation (FIBA) men’s world championships were held in 1950, and the women’s three years later.

The USA won every Olympic tournament through to Munich 1972, when the USSR beat them to gold. Yugoslavia would take the title at Moscow 1980, while the Soviets returned to the top of the podium in Seoul eight years later. Professional athletes were admitted in most sports at Barcelona 1992, where the USA’s all-star Dream Team blew away the opposition and re-established American supremacy on the court.

Women’s basketball was added to the Olympic program at Montreal 1976. The USSR won the first two gold medals in the event before the USA embarked on a victorious streak which has only once been interrupted – by the “Unified Team” which competed in Barcelona in 1992 (as a temporary successor to the USSR).

The sport continues to experiment with exciting new formats; 3x3 basketball, a fast-paced variation of the game, debuted at the Youth Olympic Games Singapore 2010 and will join the official program at Tokyo 2020.

Over the following two decades, basketball’s growth was exponential. The USA’s professional basketball league, the NBA, was founded in 1946, while the first International Basketball Federation (FIBA) men’s world championships were held in 1950, and the women’s three years later.

The USA won every Olympic tournament through to Munich 1972, when the USSR beat them to gold. Yugoslavia would take the title at Moscow 1980, while the Soviets returned to the top of the podium in Seoul eight years later. Professional athletes were admitted in most sports at Barcelona 1992, where the USA’s all-star Dream Team blew away the opposition and re-established American supremacy on the court.

Women’s basketball was added to the Olympic program at Montreal 1976. The USSR won the first two gold medals in the event before the USA embarked on a victorious streak which has only once been interrupted – by the “Unified Team” which competed in Barcelona in 1992 (as a temporary successor to the USSR).

The sport continues to experiment with exciting new formats; 3x3 basketball, a fast-paced variation of the game, debuted at the Youth Olympic Games Singapore 2010 and will join the official program at Tokyo 2020.